All About Childhood Ear Infections

Ear infections are one of the most common childhood illnesses. About 70% of all children have one infection by age three, and a third of these children will have multiple ear infections. Ear infections are a source of concern because they can lead to hearing loss and speech development delays in young children. The annual cost of treating ear infections in the United States exceeds $3.5 billion.

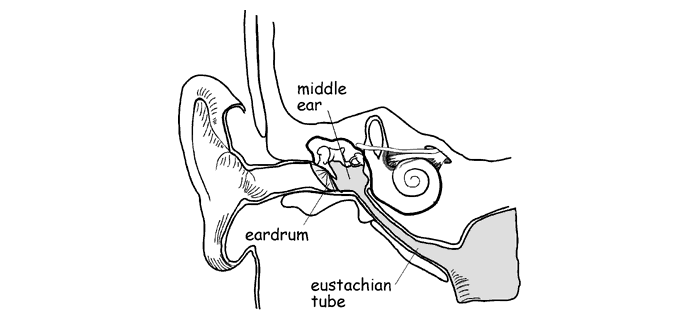

To understand the causes of ear infections, you need to know how the ear is put together

The ear is divided into three sections--the outer, middle, and inner ear. The eardrum is a thin membrane separating the outer and middle ear. The middle ear, and air-filled space, is located behind the eardrum. The eustachian tube connects the middle ear to the back of the nasal passages. Three tiny bones connect the eardrum to the inner ear, and these bones interact with the eardrum to control hearing.

The middle ear is where most infections occur in small children. Your pediatrician may use the words otitis media or fluid in the ear to refer to your child's ear problems. But parents should know that two different types of otitis media commonly affect children, and that fluid in the ear is not always a sign of infection.

Ear infection (acute otitis media)

When the eustachian tube becomes clogged or swollen, bacteria-containing fluid from the throat and nasal passages can accumulate in the middle ear. Trapped there, the bacteria multiply and lead to the formation of pus. As pressure builds up, the delicate eardrum bulges and becomes painful.

The fluid prevents the eardrum and middle ear bones from moving normally, making it difficult to hear well. If the eardrum ruptures, pus leaks into the outer ear. Signs of ear infections include ear pain, fever, irritability, or dizziness. Infants may give more subtle signs, such as ear pulling and head shaking. Infections most commonly occur in just one ear, less frequently in both.

Glue ear (otitis media with effusion)

The middle ear can also fill with fluid without the symptoms of active bacterial infection. Usually, both ears are involved. This condition may follow an ear infection, and the fluid can last for months. Although otitis media with effusion is not usually painful, it will affect a child's hearing. Very young children with fluid in the middle ear may experience speech delays, but there's no medical consensus on whether this has any long-term affect on their speech development.

Susceptibility

A young child's eustachian tubes are small and level, and nasal fluid enters the middle ear fairly easily. As we age, our eustachian tubes slant downward, making drainage more efficient. Bottle-fed babies, especially those who drink while lying down, are more likely than breastfed children to develop ear infections. Otitis media is not contagious, but it often follows colds and similar illnesses. Children exposed to colds and the flu at daycare are at a greater risk for otitis media, as are children exposed to cigarette smoke. Genetics is important in determining susceptibility, as infections tend to run in families.

Conventional Medical Treatment

Acute ear infections are commonly treated with acetominophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) for fever and pain relief, and doctors usually prescribe antibiotics to kill the bacteria. A 10-day oral course of amoxicillin is the most frequent treatment for infants, and a 5-7 day treatment may be prescribed for older children. In 1998, the FDA approved Rocephin, a single-dose injectable antibiotic as an alternative to oral antibiotics.

Some children have recurrent ear infections. Doctors may prescribe low dose, long term antibiotic treatment for these patients. In severe cases, making an incision in the eardrum (myringotomy) and inserting tubes through the eardrum to drain the fluid is the next step. This surgical procedure is performed under general anesthesia, and it's normally a method of last resort. The procedure gives immediate relief in most cases.

The medical treatment of otitis media with effusion (glue ear) is surprisingly simple. In about 60% of all cases, middle ear fluid will go away with no treatment within three months. By six months, 85% of all cases clear up without treatment. Giving antibiotics may speed up the recovery time somewhat, and can also decrease the chances of infection occurring, but is not recommended in most cases. There is a good consensus among doctors that steroids alone, antihistamines, tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy are inappropriate treatments for otitis media with effusion.

Are antibiotics necessary?

There is controversy in the medical community over the routine use of antibiotics to treat acute otitis media. The emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a major public health problem, and most of the antibiotics prescribed for young children are given to treat ear infections. The Mayo Clinic reports that up to 70% of acute otitis media cases resolve without medical treatment, and recommends that parents consider home treatment for children diagnosed with mild, non-recurrent acute otitis media. Warm compresses applied to the ear, keeping the child upright, and giving acetominophen or ibuprofen help to keep the child comfortable until the infection subsides.

A 1997 Journal of the American Medical Association article describes a treatment approach that has been used widely in the Netherlands since 1990. Children are treated for pain and fever, and observed carefully. Infants under two years of age are examined after 24 hours for signs of improvement, and older children are re-evaluated after three days. Antibiotics are offered then if needed, and also given earlier if the symptoms worsen. Routine treatment with antibiotics is recommended only for children with pus drainage, a history of repeated infections (three or more in 18 months), and children with myringotomy tubes. However, since close observation and follow-up are central to this Dutch treatment standard, patients must have immediate access to health care, a situation that may not be the norm in other countries.

Allergic Causes

Otitis media is commonly associated with colds. Since colds and allergies can have the same physical effects on the ears and nasal passages, many experts suggest that allergies are the culprit behind some cases of otitis media. If a food allergy is suspected, eliminating milk and milk products, chocolate, tomatoes and tomato products, citrus, sugar, wheat, and/or eggs from your child's diet may be helpful.

Viral Causes

Doctors have long known that viruses are often present along with bacteria in the middle ear fluid during acute ear infections. The effect of these viruses on the course of infection has been unclear to researchers. A recent New England Journal of Medicine article (Heikkinen et al, 340:312, 1999) suggests that some viruses are carried into the middle ear passively in nasal secretions, causing little harm. But others, particularly respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), actively invade the middle ear tissue, causing inflammation and pain. Vaccines that protect against RSV are likely to be available soon. If the findings of this study are correct, the incidence of ear infections should decrease when RSV vaccines are in common use.

Practical Suggestions

The best way to determine the appropriate treatment for ear infections is to be informed about the options, and to work with your doctor to develop a plan that meets your child's specific needs. You may want to track your child's ear infections by recording the date, diagnosis, and treatment of each infection. Learn the differences between acute infection and the presence of middle ear fluid without infection. Try home remedies, but keep an open mind with regard to antibiotics; they may be unnecessary in many cases, but are needed in others. Like all parents, your ultimate goal is to keep your child healthy.

Information for this article was obtained from these sources:

This article © 1999-2017 Kate Traynor, used by permission.